The Asus ROG Flow X13

My hunt for a new laptop has finally concluded

I’ve been on the lookout for a new laptop for a while now. While the HP Envy was good—is good—the measly 8 gigs of RAM was struggling to hold in all the beefy stuff that I run these days (skaffold, k3s, etc.). And it being a “budget” laptop of its time didn’t do its chassis any favors—the bottom was very scratched because the rubber bumpons came off; the keyboard deck had some rather mysterious scuff marks. Anyway, off I went looking for a replacement.

My requirements for a laptop are somewhat specific. From the title it’s obvious that I’d like to have good Linux support; here’s a list of other things that I expect to see:

- HiDPI: Any resolution above 1080p (or 1200p). I look at text all day, and I’d like it to be crispy.

- 13” - 14”: I don’t like overly large or heavy laptops. I think 13.3 inches is the perfect screen size; 14 is a compromise.

- A decent CPU: I don’t really do anything very compute intensive, but an i7 or a Ryzen 7 should be ideal.

- 32 GB RAM: Having struggled with 8 gigs for so long made this a hard

requirement. Never again will I have to

pkill gopls.

I can’t say I had a specific budget in mind, but anything more than 140k INR (1.4L, ≈1800 USD) is somewhat hard to justify. Listed below were the contenders for the prestegious position of being my laptop of choice:

- Tuxedo InfinityBook Pro 14: While this ticks all the boxes, the cost including shipping (as of this writing) is about 1700 EUR. And that’s without opening the massive, stinky can of worms called Indian Customs. Expecting a very lenient 40% duty, it’s safe to say it’s batshit expensive.

- ThinkPad X13: Lenovo’s site allows you to customize orders for certain models, and these will be custom built and shipped from China. The nice thing is Lenovo takes care of the customs and shipping and other logistics. The not-nice thing is it takes a minimum of 12 weeks—at least for the X13. That’s 4 whole months. I think I’ll pass.

With that preface out of the way, the machine I finally settled on was (as the title reads) the Asus ROG Flow X13. My model set me back by about 130,000 INR (1.3L, ≈1700 USD). The trick was to look in the “gaming laptops” section, because this model didn’t show up anywhere in the thin-and-light/productivity/ultrabook searches. And it doesn’t look gamery at all. Here’s what my Dad had to say, as a serial ThinkPad user:

“It looks like a ThinkPad.”

hardware

I opted to buy the 2021 model because, really, the only difference in the 2022 model is the marginally better CPU and a MUX switch. I don’t care much for either. The octa-core Ryzen 9 5900HS has more compute power than I could ever need.

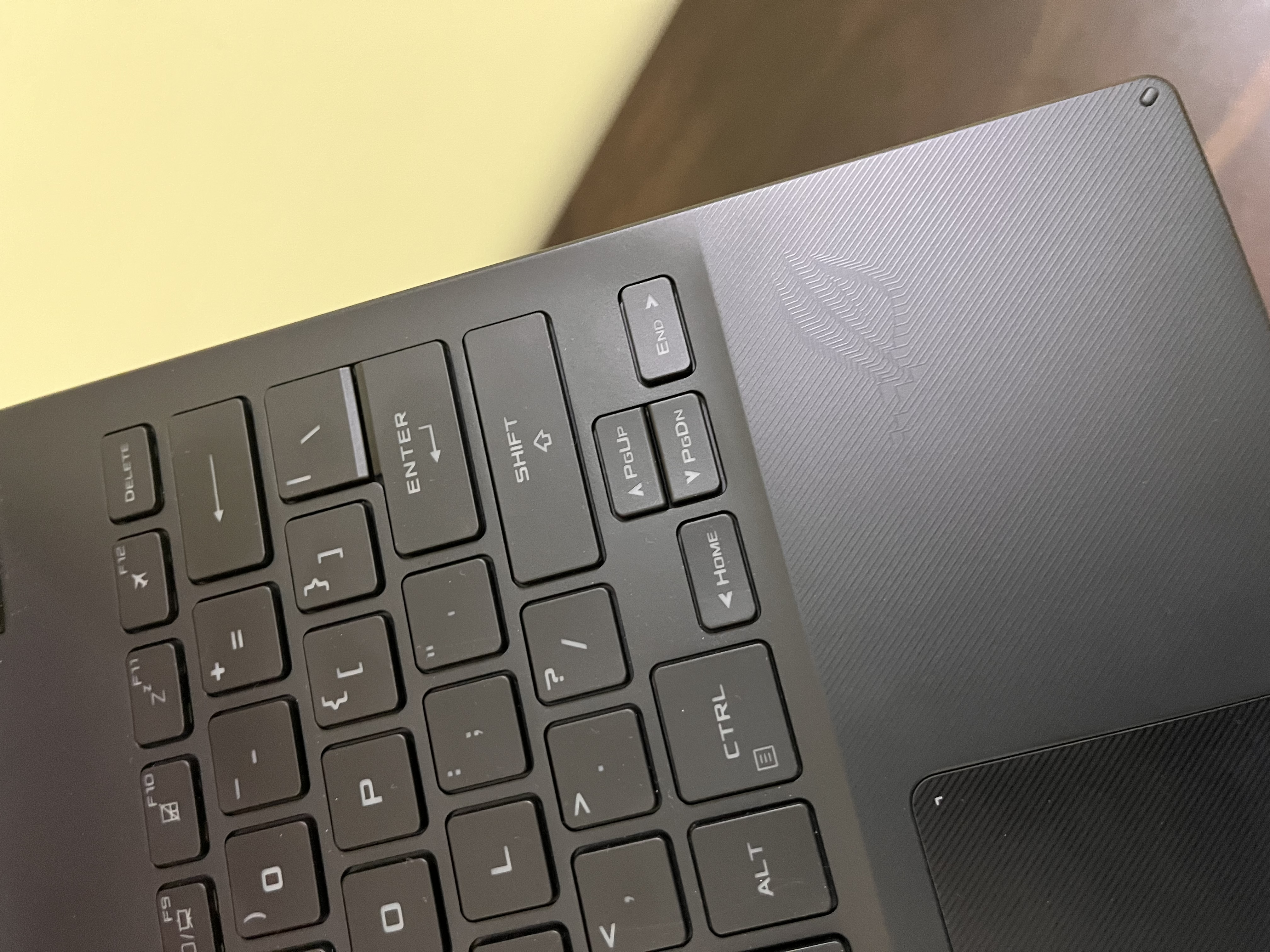

The chassis is made of a “magnesium alloy”, with a grooved finish that feels very nice to touch. There’s very minimal branding—one somewhat “iridescent” label with the Republic of Gamers logotype on one corner of the lid, and the ROG logo on the right palm-rest, made out of the same groove design.

|

|

The hinges are sturdy and allow for 360° rotation. The lid can be opened with a single finger, which is much appreciated. The screen itself is a gorgeous 4K (3840×2400) touch screen panel. While the need need for 4K on a 13” screen is questionable, I welcome it wholeheartedly. It is the best screen I’ve used; the colors are punchy, text is (naturally) very crisp. It’s glossy, and attracts a ton of fingerprints. A stylus is included in the box—or at least it was for me—but I haven’t found much use for it after the initial excitement.

The keyboard is pretty good. Given the choice, I wouldn’t have picked

the font on the caps, but I suppose it could be worse. Three backlight

modes for low, medium and high brightness exist. These can be controlled

via the sysfs device at /sys/class/leds/asus::kbd_backlight/. The

dedicated volume buttons are nice and work out of the box; the mic-mute

toggle key however needs special treatment to get detected by X11—adding the below udev rule did the trick:

udev.extraHwdb = ''

evdev:input:b0003v0B05p19B6*

KEYBOARD_KEY_ff31007c=f20

'';

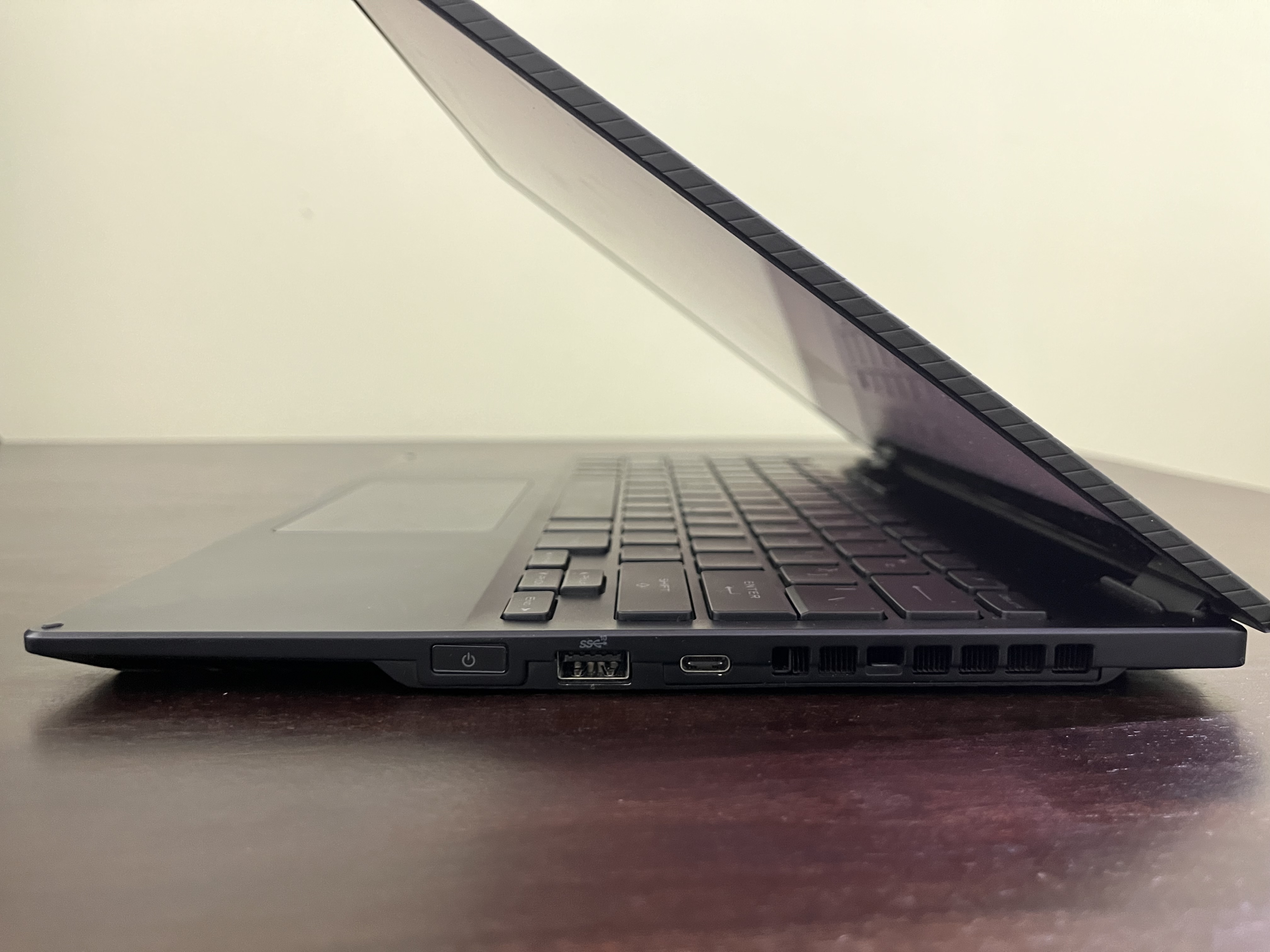

For ports, you get a USB-C and a USB-A on the right along with the power button; on the left: a 3.5mm headphone/microphone jack, a HDMI 2.0 port, and the proprietary XGm port for use with the XG Mobile external GPU. The eGPU port, while being generally useless to me, also happens to contain a USB-C port, bringing the total to two. The ports selection could be better—a single USB-A is one too less, forcing me to have to use a dongle to connect both my keyboard and mouse.

|

|

The entire package weighs in at about 1.3 kilograms, which is just as much as my HP Envy. For how well it’s built, I’m not complaining.

Finally, here’s the full spec list:

- Ryzen 9 5900HS, 8 cores & 16 threads

- 32 GB LPDDR4X RAM @ 4266MHz

- Nvidia GeForce GTX 1650 Max-Q, 4 GB GDDR6

- 1 TB SSD

software

Installing NixOS was straightforward. Basically everything works out of the box. I’d have liked to run OpenBSD on it, but I unfortunately require Linux for work. NixOS, while I understand nothing of Nix (the language), works well enough. Being able to configure your entire system from one single place is quite nice. Overall, it’s a lot more cohesive than other Linux systems.

The Nvidia GPU is handled surprisingly well. Looks like Linux has improved a lot in this regard. “Offload mode” is especially neat—you can selectively “offload” certain tasks (like running Steam) to the GPU, and otherwise have it suspended. Here’s how I do it:

{ pkgs, ... }:

pkgs.writeShellScriptBin "nvidia-offload"

''

export __NV_PRIME_RENDER_OFFLOAD=1

export __NV_PRIME_RENDER_OFFLOAD_PROVIDER=NVIDIA-G0

export __GLX_VENDOR_LIBRARY_NAME=nvidia

export __VK_LAYER_NV_optimus=NVIDIA_only

exec -a "$0" "$@"

''

Now simply run

$ nvidia-offload steam

to have Steam run on the GPU. Use the nvidia-smi tool to inspect

processes currently using the GPU.

The laptop has an accelerometer to detect when it’s in tablet mode, and invert the display accordingly. Unfortunatly, I couldn’t figure out how to get it to work in X11/cwm. Instead, I wrote a handy script to rotate the display and the touch input:

{ pkgs, ... }:

let

xrandr = "${pkgs.xorg.xrandr}/bin/xrandr";

xinput = "${pkgs.xorg.xinput}/bin/xinput";

in

pkgs.writeShellScriptBin "invert"

''

orientation="$(${xrandr} --query --verbose | grep eDP | cut -d ' ' -f 6)"

if [[ "$orientation" == "normal" ]];

then

echo "turning screen upside down..."

${xrandr} -o inverted

${xinput} set-prop 'ELAN9008:00 04F3:2C82' 'Coordinate Transformation Matrix' -1 0 1 0 -1 1 0 0 1

${xinput} set-prop 'ELAN9008:00 04F3:2C82 Stylus Pen (0)' 'Coordinate Transformation Matrix' -1 0 1 0 -1 1 0 0 1

${xinput} set-prop 'ELAN9008:00 04F3:2C82 Stylus Eraser (0)' 'Coordinate Transformation Matrix' -1 0 1 0 -1 1 0 0 1

else

echo "reverting back to normal..."

${xrandr} -o normal

${xinput} set-prop 'ELAN9008:00 04F3:2C82' 'Coordinate Transformation Matrix' 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1

${xinput} set-prop 'ELAN9008:00 04F3:2C82 Stylus Pen (0)' 'Coordinate Transformation Matrix' 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1

${xinput} set-prop 'ELAN9008:00 04F3:2C82 Stylus Eraser (0)' 'Coordinate Transformation Matrix' 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1

fi

''

Then, simply run invert to toggle your current orientation:

▲ invert

turning screen upside down...

▲ invert

reverting back to normal...

Battery life could be better, but with TLP/powertop + switching the CPU

governor to powersave on battery, I get about 7 - 8 hours on light

workloads, and about 5 on heavy. I’m going to guess the 4K panel is to

blame.

Also worth mentioning is the Asus Linux project. They have some useful resources for running Linux on Asus laptops, and asusctl / supergfxctl—two great tools for managing power profiles, fan curves and the dGPU.

Overall, I couldn’t be happier with this machine. It wasn’t cheap, but it sure does check all the boxes and it’s incredibly future proof. As for my trusty old HP Envy 13, I haven’t decided yet what to do with it. It’ll most probably end up in my closet, enshrined under a layer of clothes.

You can find all the scripts mentioned in this post (and more!) here.